Using quality and productivity tools

This is a compilation of past articles, presented in no particular order:

- Process mapping: a step by step guide

- Don’t just listen: giving a hand to “the voice of the customer”

- Cultural change

- Project post-mortems

- Testing, testing

- Pareto charts

Also see our surveys page and “how-to” for solving old problems and getting fast action.

Process mapping: a step by step guide

Process (work-flow) mapping lowers errors, increases effectiveness, and enhances communication. Process mapping sessions may result in sudden revelations such as:

- “I didn’t know you did it that way, we do it this way!”

- “But why don’t we do it that way instead?”

- “No wonder it takes so long / goes wrong so often!”

There are several preconditions for effective process mapping:

- The process(es) to be mapped must be specifically defined before the meetings start.

- The authority of the team must be delineated as well. The more authority the group has, the more motivated people will be, and the more changes can be successfully made. This means that the people who are actually responsible for making changes must be present and part of the process.

- High-ranking team members must try to draw out the others, using silence, questions, and positive feedback to increase participation.

- The team should consist of about five to twelve people, preferably about seven; and it should have representatives of all groups and all levels involved in the process.

- A process consultant should be on hand. The process consultant does not focus on content, but on how the meeting proceeds. The process consultant can greatly reduce the time needed for the meetings, while increasing the quality of decisions.

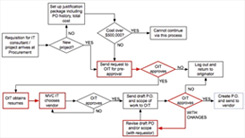

There are several phases in the process mapping sessions:

- Diagram (map) the way work is currently done, using a flow chart to graphically portray the process. Members who come up with ideas for improvements should write them down and wait for the next steps.

- Identify problem areas to concentrate on (circling the areas in red may help).

- Create possible action steps — but postpone judgement; the emphasis should be on generating ideas and writing them down on charts all can see.

- Evaluate action steps and select those which are fastest and easiest to implement, and have the most significant effects. The others should be held for future meetings.

- Make one team member responsible for each action step.

- Set firm follow-up and completion dates, including a date for the next meeting.

- Periodically meet again to discuss progress and new issues, and to check that actions are being implemented. Meeting every two weeks will improve follow-through.

Although process mapping uses large quantities of flip chart paper, if some steps are quickly implemented, it is a motivator for change which can quickly improve effectiveness. If changes are not implemented, or no feedback is given, the result will be lower trust and morale, and higher resistance to change. When a change cannot be implemented, the reasons should be quickly and clearly communicated to the team.

Don’t just listen: giving a hand to “the voice of the customer”

For decades, people have talked about listening to the customer. Yet, our systems seem as bad as ever. Are we listening?

I would argue that we’re listening… we’re just not taking the right actions.

Once, I helped to present the results of an employee survey; we mainly left it to them to develop action plans — the best way to instigate change. There was some brief discussion, and then the president of the company said, “Why should we care about any of this?”

All heads turned to him. Then to me as I started explaining why I should care. It turns out the president just assumed employees only cared about pay and benefits, and everything else was irrelevant. In my experience, that’s sometimes true — usually, with salespeople — but it’s usually not. After all, there’s no shortage of people who work for less money than they could.

A few months later, the president found another job, but that led to the question of why he would even allow the survey to waste company funds if he had no intention of acting on the results (there was a chief executive above him, who did value the survey results, did act on them, and may have had something to do with the departure of the president a few months later).

It’s not uncommon, though. There is no shortage of companies who tap customers and employees with market research and surveys, and then do nothing with the results, or use them to justify actions they would have done anyway. To this I say: it’s better to take some action based on the data, but if you’re not going to, don’t waste time and money getting the information in the first place.

There are many ways to use employee input; Toyota, for example, has committees that seek employee input, and then, if the suggestion is at least cost-neutral, often empower that person to make the changes, so they will actually get done. One of the rules, at least in past years, was that increases in efficiency wouldn’t result in immediate job losses, removing one source of fear. A bias for action on employee input is invariably part of any self-improvement program.

You don’t need to survey customers to make improvements; you can just listen to what people are saying (both customers and employees), and do something about it. I recently had to contact someone at a company I dealt with; each rep had a telephone number in their email signature, but none of those actually worked. Nobody had thought of changing the email signatures to match the “new” (a few months old) phone system. Two weeks after I told them about it, nothing had changed, and I changed vendors — what else were they missing?

You don’t need to survey customers to make improvements; you can just listen to what people are saying (both customers and employees), and do something about it. I recently had to contact someone at a company I dealt with; each rep had a telephone number in their email signature, but none of those actually worked. Nobody had thought of changing the email signatures to match the “new” (a few months old) phone system. Two weeks after I told them about it, nothing had changed, and I changed vendors — what else were they missing?

Most outfits with call centers get a flood of customer information, sometimes dealing with product issues, but sometimes indicating problems with the company’s internal processes (such as mis-programmed voice prompts, or leaving out a common problem). The clever company collects both kinds of information, and has a way of quickly taking action to fix problems and streamline processes.

It’s common for organizations to make mistakes, because people make mistakes, and organizations are groups of people with some rules. What separates the best from the worst is how quickly they fix the mistakes — and part of fixing mistakes is listening and doing something with what you hear.

Cultural change

Cultural change efforts seem to fail as often as they succeed, partly because it’s neither easy nor fast — just brutally effective. Cultural change requires concentrated and focused effort over the long haul, a widespread belief that change is necessary, and the willingness to critically examine current beliefs, values, and practices.

In 1997, Chrysler was an oft-cited example of a company which had used cultural change to suddenly regain a leadership role, changing the way almost everything in the company was done within a few short years.

The impact was not quite so dramatic in the dealerships. Surveys showed that customers stayed dissatisfied with North American Chrysler dealers; because these independently-owned businesses had no urgent need for change, once the company’s reversal of fortune became clear. Increased sales made dealership owners complacent… until Daimler took over and the company declined again.

The same power that makes cultural change so effective also makes it hard for people to abandon their customs and beliefs. Unless there is a clear and pressing need for change, there will be people who do not test their beliefs and customs. Managers can try to push changes through with sheer force of authority, but that may only stiffen resistance. Personnel changes, likewise, should be a last resort.

The first step, then, is to try to convince people of the need for change. This may involve running focus groups in the presence of key people, going over financial or statistical data, using outside surveys or reports, or benchmarking against competitors. There are many ways to get participation, but each requires respect. It is harder to win people over without respect for their intelligence and their traditions, or without trying to understand their views.

Resistance to change

It can be hard to respect those who are blocking your progress; certainly, it is easier to think of them as “resisting,” “stick-in-the-muds,” or “just not able to get it.” But there are often powerful reasons for their lack of participation. For example, people may be afraid they will work themselves right out of a job; and there have almost always been failed initiatives in the past.

There are reasons why some people resist change. The keys to acceptance are truly understanding their concerns, working to accommodate their needs and truthfully allay their concerns, defuse the emotions, work with the facts, and work with people instead of around or through them. This may sound like common sense, but in a tight schedule, with our enthusiasm for new ideas and ways of doing things and our own belief that we must be right, it is easy to overlook other people’s concerns.

In many cases, the people who resist change have valid points which may, once you understand them fully, cause you to change or fine-tune your plans. I have often found that people who did not express the reasons for their resistance well (or at all) had quite valid objections which, when considered, greatly improved the outcomes.

The rewards system

Possibly the most significant obstacle is the reward system. W. Warner Burke wrote that he has abandoned consulting jobs when the rewards system was placed off limits, because it would prevent his success.

The pay, promotion, or bonus system may, in reality or in perception, discourage any change. The maxim “you get what you pay for” (or “you get what you reward”) is as true in organizations as it is in the lab. (This is not necessarily because people are greedy and motivated solely by cash; a company’s reward system may be seen as showing its true intentions, while everything else is “just words.” The cliche: “put your money where your mouth is.”)

Social issues

Another important factor that is often overlooked is the social system. Changes in English coal mines once led to a strike, because it broke up the working groups of miners; they resisted to keep their social system alive. If you work with the social system, or convince people that they will not lose the parts of it they value, you will be more likely to get everyone’s support – which is essential for a successful change.

Working around myths

Myths are a way we simplify life and prevent ourselves from being overwhelmed with information and decisions. They may or may not have been born in truth, but, with time, they tend to lose their relevance and become a block to progress.

Myths both explain reality and to support social systems; and they may not be compatible with the new culture. Therefore, one essential step in cultural change is to find and work with (or debunk) myths — or to refit the myths so they support the new world — or to slip in new myths that support where you’re going next (e.g. finding new stories about the founders). Some companies have been quite adept at “making up history” or at least using careful choices, to create inspirational myths.

Debunking myths can be very difficult. One way to do this it have the believers involved in the process of getting information to counter the myths. For example, at one auto company, one of the managers of the central customer service center believed that customers were perfectly happy with the center’s service levels and did not want any other way to contact the company. His proof: “if there were any problems, our dealers would tell us about them.” To obtain this manager’s (and other like-minded individuals’) buy-in, the myth of the perfect service center and the contended customer had to be dispelled.

Some common myths have a grain of truth, but the math is wrong: the customer who is never satisfied, the apathetic or lazy employee, the people who mindlessly resist change, etc. There are people who fit those descriptions, but rarely so many as the myth portrays.

Many of the people put into those pigeon-holes are there because of self-fulfilling prophecies: if the employees act like a customer will never be satisfied, the customer will perceive it at some level, and it will cause dissatisfaction. If staff are treated as though they are lazy, they will resent it, and will act according to expectations. When managers believe employees will mindlessly resist change, they do not take the steps needed to involve people (or do not take them seriously enough), and people will resist.

Each company or organization has its own myths. Some are common across many companies; some are unique. They are usually not very hard to find, especially for outsiders; this is a good opportunity for a student internship!

Wrapping up

Cultural change isn’t easy. It is powerful, but if treated like just another management fad, or if forced through like a steamroller, it won’t work. If you want to change the culture, you have to:

- Show a pressing, urgent need

- Reduce perceived threats to the employees

- Work with the current culture, re-using or ending myths

- Preserve desirable aspects of the existing social systems

- Make sure the reward system does not run counter to the new culture

- Discover and analyze the causes of resistance and work around them

Project post-mortems

Have you ever noticed your group making the same mistake over and over? (Or perhaps your customers have noticed for you?)

Personally, I hate making mistakes. I think I’ve stunned a few vendors when we dug through a problem and found it was their fault. They were expecting to be yelled at, but I was too relieved at not having made the mistake myself. For that reason, long ago, I started the practice of project post-mortems for just about everything I was involved in — including a weekly student newspaper.

It’s important, at the end of any project, to stop and ask:

- What did we do well — what should we keep doing?

- What did we do badly? Do we need to fix it or was it just bad luck this time?

- What can we do better?

That said, there’s an even more important thing to do than that:

Write it down.

Make a punch-list of things you learned from the last time. Change processes right away, if possible, to make things work better in the future. Never wait for things to calm down, because then the ideas are forgotten or the initiative is lost. Do it now — strike while the iron is hot.

You can even act on what you did well, because there could be a chance to do it even better, or to do something else the same way.

Older readers may remember a TV show called “Quincy, M.E.” The episodes did not end when Quincy, the coroner, found out the cause of death. Each week, he badgered the city’s (apparently) sole police detective, or various never-seen-again officials, into fixing the problem, whether it was toxic waste or a killer. Quincy did not just do his job, have a beer in (apparently) the world’s only bar, and go to sleep; he tried to make sure it could never happen again. That is our job as consultants, managers, or even as freelancers. Figure out what we did well and what we did poorly, and make sure we do better next time.

The path to flawless efficiency is from not just making mistakes, or learning from mistakes, but putting your new-found knowledge to work. After every project, do a post-mortem — and then take action.

Constant testing

When I first started in the employee survey business, I was responsible for some big mistakes. Eventually, I realized that anything we did not test would go wrong; and that it wasn’t just testing that mattered, but testing thoroughly and intelligently. The latter realization came after an Excel copy/paste bug — where the first 20 and last 20 cells were correct, but everything in the middle was just a repeat of the first 50 or so cells, over and over.

Sadly, that’s not unique to surveys. As one example, back in the 1980s, an automaker launched a critical series of new engines. They had been through endurance testing in extreme weather conditions — but they soon started getting a flood of seized engines at the dealerships. The problem: the company saved money by buying a single brand of oil for testing. Many dealers and owners used inferior oils that thickened in the cold much more than they should have (due to high paraffin content). Engineers quickly changed the design to deal with glue-like oil, and the engines developed a good record for longevity.

Lesson learned? Not quite. Thirty years later, they made almost the same mistake again, this time with gasoline. There are different gasoline formulations in different states, and different brands of gasoline have different additives. The company used a single brand, again to save money, and despite thorough testing, ended up with an embarrassing and expensive problem — the heads of certain engines, when used with certain gasoline under certain conditions, would crack.

Between those failures of testing were many others — some as products were rushed into production, some because people didn’t ask the right questions about them. Billions of dollars were lost to poor quality — in warranty costs, incentives, and extra advertising and marketing to cover cars no longer seen as above-average in reliability.

Some products seem to lack any testing at all — particularly web sites and other software. In some cases, this is because all testing was done on a single operating system and web browser, and sometimes only on a single type of computer and monitor. That can result in a web site that only works for fifth of their customers (or potential customers) — or which breaks as soon as the operating system is updated (such as any web site “designed for Internet Explorer 6”).

One form of testing is watching someone try to use a product — even an employee survey. You can quickly spot problems as people try to do things in ways that were unforeseen, interpreting directions differently or ignoring them entirely, missing major user interface features, and such. Major and minor corporations and government agencies alike often seem skip these tests, or to test with “people of convenience” who may be too familiar with their group’s way of thinking, or other versions, or past versions. That can result in big problems down the road — as in one organization, where a critical control was not even visible on the screen of most people.

One form of testing is the “mystery shopper” approach, even if done without actual mystery shoppers. Try contacting your own company (or agency or university) with a problem — particularly one requiring human contact. See how the phone system works — does the introductory message take so long that, if you were a real customer/citizen/student-or-instructor, you would be ready to clobber the first person who answered the phone? Do the choices make sense? Is one appropriate? Do they actually work? The same approach can and should be used for most user interfaces, whether on a computer, a dashboard, or in a company lobby.

It’s slow and mildly expensive to test everything thoroughly. It’s even more expensive and time-consuming to re-do and repair things that could have been done right the first time, and to lose or enrage customers.

“If it’s not tested properly, it’ll go wrong.” That became the paranoid mantra of our consulting practice, and it served us well for many years. Perhaps it could serve your organization well, too.

Pareto charts

Pareto analysis is a simple way to figure out the major causes for a problem. Though it’s mostly used by quality assurance people, pareto analysis is also useful for organizational development, because it is common in manufacturing (so many people are used to it), and because it is a clever system.

Typically, Pareto analysis is used both to kick off problem solving by helping to identify root causes (the basic, underlying issue which is causing the problem, as opposed to the “apparent” issue which may, in itself, be caused by something else – for example, replacing a defective voltage regulator which is allowing batteries to be damaged, rather than simply replacing the batteries).

Pareto charts are useful because most problems tend to come from one or two processes or components, rather than from a large number of causes. It is, simply, a histogram, laying out categories (process or material problems) versus the number or proportion of problems, with a (rather unnecessary) curve showing the cumulative percentage of incidents.

The hard part is collecting the information, and distilling it into useful categories — that is, categories that make it easy to figure out how to resolve the problem. Categories are shown in descending order, so that the most common issue or process shows up first. The categories should be specific enough to be actionable. In our quick-and-dirty example, “employee error” isn’t elaborated on because it’s not a major issue, compared with the first three items — two of which could be considered employee errors on their own.

If no clear cause appears, you can change the categories to see if that works. Otherwise, the first few bars should generally be targeted.

Mission statements

Many companies have spent a lot of time and money creating a mission statement, presumably to align employees around a common vision and organizational goals. Like most management fads, mission statements became very popular for a period because of some success stories. There are companies that have used mission statements, or similar documents, to great effect: the Johnson & Johnson Credo comes to mind as a great unifier for the federation of J&J companies.

But most mission statements seem to fail, becoming nothing more than a wall ornament.

For the most part, the reasons for failure are the same reasons why many organizations do not find great success in balanced scorecards, reengineering, job enrichment, empowerment, and a score of other fads that are highly effective for some, weak for others, pointless for others. Those reasons are:

- Fuzzy, nonspecific language

- Interchangeable goals or visions that can be adopted by any company if only a few words are changed

- Lack of true, prolonged leadership support - in action more than in words

- Poor implementation

The organizational mission statement should say why the company is in business (make the best widget? Make the most money off of widgets? Maximize shareholder value? Provide jobs to the community? Make the world safe for widgets?), how it intends to fulfill its primary function (make the best widgets through continuous improvement OR make the best widget through constant research and development), and, ideally, what its key values are.

A useful mission statement is very brief, understood by everyone, specific, and actionable in that you can use it to make decisions. A normal mission statement is vague and covers all the bases. But few companies can be the best in research and development (innovative product), quality, cost, AND marketing.

Most important, a good mission statement is the credo of the organization's leaders. If the leaders make decisions on a daily basis that reflect the vision and methods in the mission statement, others will eventually follow.

Making a concerted effort through training of new and existing employees, measurement via survey or interview, and willingness to adjust parts of the statement as needed will go a long way towards making a mission statement an effective tool. However, be warned that implementing and sticking to a mission and vision is a long term effort. Johnson & Johnson made its credo strong by working hard for decades; though it is ingrained in the culture, if the leaders of J&J were to ignore it for a few years, we suspect the J&J companies' cultures would lose their rudder and, with it, some of their unduring success. (Note: this seems to have happened.)

This page used to be several different pages. We present them here in no particular order.

Copyright © 2001-2024, Toolpack Consulting, LLC. All rights reserved.